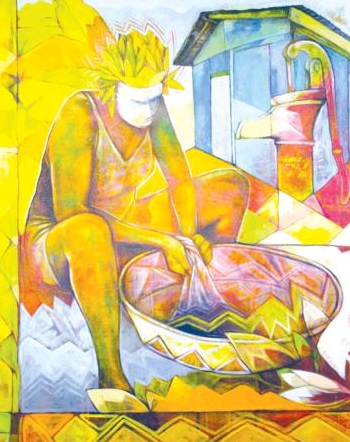

'The Home We Share' (2015). Jackson Petit. Featured in the NAGB's permanent exhibition 'From Columbus to Junkanoo' seen alongside Herring's work. From the D'Aguilar Art Foundation Collection.

Art is always unique to a place and art also has a unique place in culture. As Jackson Petit and Peggy Herring illustrate in their capturing of local color, the disparities are real. Herring’s ‘Five Children at a Water Pump’ painted in 1984, a part of the NAGB’s National Collection, and Jackson Petit’s ‘The Home We Share’ 2015, a part of the D’Aguilar Art Foundation, articulate a 3-decade difference but depict little if any real change in many Over-the-Hill communities. Paradise may loom large and eclipse these areas but the reality that remains is captured and immortalized in paint on canvas.

I wish to call up the nightmare of Nobel Prize-winning Trinidadian author V. S. Naipaul as I venture through this piece, not because I am in total agreement with his position that but because it pronounces so much of the contempt that we hold for what is ours.

“[n]othing was created in the British West Indies, no civilization as in Spanish America, no great revolution as in Haiti or the American colonies. There were only plantations, prosperity, decline, neglect: the size of the islands called for nothing else.” (The Middle Passage, p. 27, 1962, Pan Macmillan)

The artworks discussed here speak a different language. They show that a huge history, tapestry, palette has been created in this small British-West-Indian island, although the size may be small, the production of art is large. Naipaul was perhaps stuck in a paradigm that was very common back then, that of those mimic men who stepped into power after the Crown abandoned its role as the direct ruler through its governors, who saw nothing but rot where they were sent for their twilight years. This was certainly the case of The Duke of Windsor, or at least Wallace’s perception.

History, however, has put Bahamian culture on the map. What we must now do is work to keep it there and we must remove the prison of the colonial gaze from our eyes and minds.

“There are certain places, small places with hardly any history to talk of... which were then left in the world. They are small; their people are not fully educated,” (David Shaftel, “An Island Scorned,” The New York Times, May 18th, 2008)

The absence of history that Naipaul comments on is not real, the lack of anything ever being created in the ‘English’ Caribbean is also not real. It is, in fact, a fantasy of a Western dominated culture. However, the limited education he disparages holds us in bondage. We must step out of ourselves and begin to realize, unpack and change the perceptions that choose to view The Bahamas as a place without cultivation, where tourism equates to culture.

Tourism is a façade created by imposing Western-styled fantasylands on a thriving country, where the majority of the population does not live in high-rise air-conditioned sterility. Where the people do not leave in May, when it begins to get ‘too hot,' but rather reside, inhabit, live in this space 24/7, 365 days of the year. Many of these people never leave the capital; others, when they live in other islands, will remain settled in their snug corner settlements for the entirety of the three score and ten years promised.

They may never venture to the third settlement north, or the fourth settlement south. However, many will be forced to come to Nassau because of development trends. Many will be forced to die in a humorless room in an unkind, vapid place in Nassau or be dragged here after death to be examined and their death approved because the infrastructure to support live and wellness has been removed from the island communities and all focus has been placed on the centralized capital.

The two works of art by Herring and Petit are truly local. They are like the Minnis family’s work, very much vivid depictions of island life, a vernacular rarely seen in kind renderings, even though we think we inhabit a metropolis.

These are some of the lessons art teaches us. It does not simply bring pretty images to speak for a people whose lives are far from pretty, who may inhabit rat-infested spaces due to lack of sanitation and poor rubbish collection. Places where "de ole truck break down again" and no other can be found, so garbage must swelter in rotting heat for upwards of a fortnight. Out of these communities arose many of our post-colonial leaders who have left their homes to dereliction and decay, where even now folk have moved in so nothing at all has changed since the 1950s. For the island that boasts Baha Mar and Atlantis, it seems unfathomable that there should be such disparate realities.

The woman in Petit’s ‘The home we share’ is faceless because she speaks on behalf of a population, her voice is seen, not heard by the officials in power. Hers could be the children at the standpipe in Herring’s ‘Five Children at a Water Pump.' The intergenerational continuity shows the lack of rupture from the colonial past. We have left poverty behind and we are on our way to being the first world, though this will never happen as long as these power struggles and asymmetries survive.

How can we talk about desegregation when there has been little change for those who still inhabit the common yard, who still tote water from the government pipe? We can see these renderings as quaint and folksy, or we can see them for what they are, lessons in inequality. They show the art of place and the place of art.

Sadly, so many of the population today, as opposed to fifty years ago, have opted out of the struggle because they are so far removed from seeing the reality and of becoming ‘something,’ of moving on up to the east side, of the kind of place Naipaul would say ‘power was recognized but dignity was allowed to no one’ (The Middle Passage, p. 43).

We have decided that all poor, black underachieving males are criminal and though they hail from these communities from whence we hailed, we will use the same laws that oppressed us to exclude and marginalize them. Color and race become solidified in the eye of the observer from a particular vantage point. The gaze either imprisons or it liberates; right now the gaze imposed on us, imprisons through the limitation of living in two worlds; one where water runs continuously from silver-plated taps, rinsing away the salt from our bodies, and the other where a communal standpipe on the corner serves the many, but there is no running water in houses.

Art captures that space of difference as well as the space of possibility. Racism is not always about color or the ethnicity of those in power, it is about maintaining the status quo. The eye of the artist sees more than is often revealed to those who choose not to venture through John Close or Dumping Ground Corner. The landscape is distinct from Western Road or Frank Watson Highway.

If we step back and gaze at the two paintings in question and juxtapose them with a drive through of Bain or Grants Towns, Malcolm Allotment, the landscape remains the same. In Podolio, Lewis Streets or Tin Shop Corner, little has changed except for the abandonment of the inner city. Many of those who remain are stalwarts and will not be moved. However, this is a cultural Mecca. A standpipe is a place for gathering; the tin tub remains a fixture in many homes that still do not have running water or an electrical meter. Other homes that may have both are disconnected because poverty has forced them to forego these essential services.

The facelessness of Pettit’s woman is a statement on poverty’s ubiquity. In the space of art, even in the face of poverty, there is massive creativity and beauty, as can be seen in these works. The gaze must liberate, as opposed to imprisoning in a world of limitations and marginalized alterity. We must break out of the duality of modern development.

The art of survival in that place and the place of art can coexist. The art of place is as much about allowing communities to develop beyond the constrictions of the firm colonial gaze. This is the only way to allow the place to be seen as art and the art of that place to be appreciated for its uniqueness. Despite Naipaul’s condescension of nothing coming from these parts and the paternalistic control on them, art flows from these spaces, even when the gaze insists on seeing them as ghettos of disrepute. In them beauty lives.

By Dr. Ian Bethell-Bennett

Click here to read more at The Nassau Guardian